When we arrived at the trailhead we were a hardy band of 16 or 17, many of whom were venturing into this high desert landscape for the first time. After several weeks of cloudy, wet and often icy winter weather in the Treasure Valley, we were primed and ready for a sunny day in the desert. The weather forecast looked to be on our side and we hoped that the recent spell of dry weather would have allowed the roads and trails of the Owyhee country to dry sufficiently.

Unfortunately, we had driven into a thick fog bank outside of Grandview. The chilly, moisture-laden air penetrated our clothing and had many of us wondering if we had brought enough layers. Also, the looming threat of wet conditions stood to dash all our hopes of venturing into this rarely visited area of Idaho.

When moisture is present in sufficient amounts in this parched, erosion-prone landscape, the silty, flourlike soil of the flood plains and river bottoms becomes a sort of sticky dough. This is cruel stuff. Part quick-drying cement, part biscuit batter with a wide assortment of stones, sticks and other detritus spread throughout, the “Owyhee Gumbo” is legendary for its ability to stick to just about anything and set hard, preventing bicycle wheels from turning and fouling all manner of moving parts.

Knowing that we may have to abort the ride if we encountered sustained muddy conditions, we unloaded bikes in a farm road turnout, made our final preparations and pedaled west on the chunky gravel to see what the day would bring.

Unfortunately, the conditions quickly deteriorated as the road entered a flood plain and made several crossings of the rutted, sloppy stream bed. These were precisely the kind of conditions we were hoping to avoid. Photos cannot do justice to the evil of this particular breed of mud.

The more experienced Owyhee travelers made their way through the rocks and brush off to the side of the main tracks. The uninitiated, stubborn or foolhardy among us charged headlong into the silty, sinking mudholes. We sunk in slop over our rims and up to our pedals. Our wheels rapidly packed with the silty, dough-like mud and scraped their way between fork blades and rear stays. Then the Owyhee Gumbo claimed a victim.

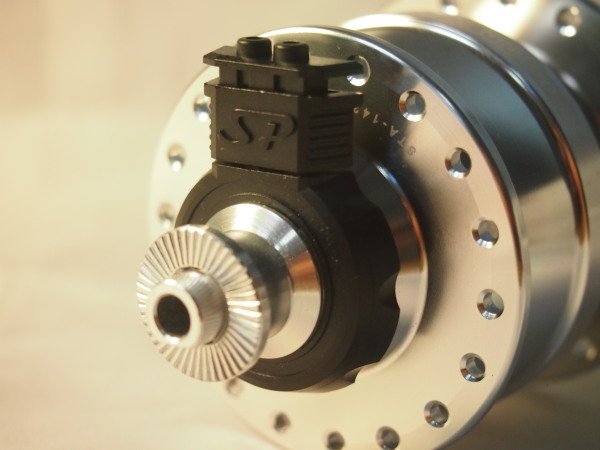

I pedaled smoothly into a deeper section of mud, coasted breifly through the worst of it and began pedaling to churn my way up the little rise from the bottom of the stream bed. I heard a snap and felt my chain lock up. Expecting a simple clog, I looked down to see my rear derailleur twisted against the rear of my cassette. The parallelogram had snapped cleanly off, leaving only the upper knuckle still attached to the hanger. Great. We were less than two miles into our ride and I was wondering if my day might already be over. As it turned out, I wasn’t the only one feeling that way.

While I set about assessing the damage and feasibility of a solution, the mutiny in our ranks was already taking place. Talk of gravel road alternatives, broken bikes and carwashes drifted through the canyon as I unbolted what was left of my derailleur and stripped off the shifter cable. I punched a pin out of my chain while other voices countered that conditions were bound to improve when we climbed out of the drainage onto the plateau above. By the time I had found a workable gear and shortened the chain to rig my machine into a singlespeed, all but seven of our once mighty expedition force had beaten a retreat back to the cars. Such is the fickle nature of desert travel, especially in the winter.

Somewhat demoralized but not yet beaten, I decided to press on and try my luck with the intrepid remaining crew: Jim, Stacy, Wendell, Star, Sal and Kurt. Afraid that my overstressed chain might snap or derail with heavy pedaling, I did my best to keep my cadence quick and light. My confidence in the ad-hoc singlespeed rig improved when it withstood a few out-of-the-saddle efforts to get over some punchy climbs. Fortunately, our planned route would climb gradually until the turnaround point, so I could expect to coast a good portion of the return leg if my repair failed and I was forced to bail at any point along the way.

As we had hoped, road conditions improved dramatically as we gained elevation. Once on the plateau, the well-graveled double track had a soft, spongy feel under our tires but did not have the same sticky, glutenous, dough-like texture we had encountered down in the wash. We picked our way around a handful of trouble spots as we pedaled our way through the fog, into the void.

We stopped briefly for a snack at a rock outcropping, hoping the sun would burn its way through the fog that clung to the sagebrush and stone. The sloping walls bordering Big Horse Basin Gap were barely visible through the haze as we approached but the suspended vapor glowed brightly with the warmth of the sun, calling us higher.

We climbed into the gap, slowly gaining elevation until we emerged in a world of light and clear blue skies.

We rode through the corridors of stone, soaking up the warming rays of the January sun and feeling wholly justified in having made it through the trials below to earn this reward.

The road wound its way through the pass, bordered by eroded rock spires and chimneys.

Finally, we emerged from the gap into the full glory of Horse Basin. Towers of batholithic rock bordered the road as we grunted up the final steep pitch to reach the next plateau.

Feeling energized by the sun and spurred on by the desire to keep my gear turning at a quick cadence, I pressed on up the road ahead of the rest of the group. Forging into new territory, I soaked up the landscape as I powered my singlespeed southbound over the rocky, rolling terrain. At the high point of our ride – 4,300 feet up on the desert plateau between the deep canyons of Big and Little Jack Creeks – I paused for a stretch and to regroup before heading down the cherrystem trail to our final destination.

Wendell, ever the enthusiastic high-desert explorer, led the descent to the canyon’s edge.

Sky followed with the rest of the crew, exhilarated by the quick descent on the cherrystem to the edge of the canyon and the wilderness beyond.

Now, where I come from back in good ol’ Dixieland, our creeks don’t look much like this. It is hard to believe that Big Jack Creek – the stream that carved this massive gorge out of the sand and rock – is only a minor tributary of the Bruneau River and not a stream with the power of the Owyhee or the Snake.

We loafed in the sunshine and explored to our hearts’ content, snacking on whatever provisions we had brought along while soaking up the unadulterated quiet. Though we may have wanted to toss out our bedrolls and stay the night, duty and responsibility called us back to the city. We would have to wait until another day to watch the stars come out over the desert. Reluctantly, we packed our bikes and pedaled back up the cherrystem to begin the return leg of the journey.

We were rewarded with a light breeze and mellow downgrade for most of our ride through the Basin, toward the gap in the rocks far in the distance. I was able to spin my gear at a quick cadence and carry easy speed but fell off the wheel of the faster descenders when things got steeper.

As we made our way back down into Big Horse Basin Gap, we were pleased to find that the fog had completely burned off in the intervening time, allowing clear views of the surrounding country that had been invisible that morning.

We used a larger helping of caution when returning through the still-sodden river bed, however. The sun had done some good work drying things out but there was still no safe line along the main path. We took to the bush on the high side of the drainage, looking for footing on large rocks to avoid the slippery, clinging batter that weighed down our bikes and threatened to come over the tops of our shoes. Finally, we emerged back onto the heavy gravel and cruised down the final dip in the road to the cars where clean clothes and cold beverages awaited. We rubbed our legs and stretched our arms in the glow of twilight, quite pleased with our day’s work. Finally, we piled back into our vehicles for the ride back to town and hatched schemes for future expeditions into this strange and beautiful country.